I thought it would be fun to share some of the science I’ve been doing, especially because it involves words. When people think of biology, they tend to think of the experiments, not the hours spent trying to condense those projects into a legible and concise piece of art.

I thought it would be fun to share some of the science I’ve been doing, especially because it involves words. When people think of biology, they tend to think of the experiments, not the hours spent trying to condense those projects into a legible and concise piece of art.

It may not be literary art, but writing good papers is still an art–you’re still telling a story. For this post, I’m going to attempt to break down a little bit of that story and also to talk about two of the fun behavioural studies I’ve been doing!

WARNING: contains big bugs, pretty graphs, some numbers, and twenty zebrafish.

What I do/disclaimer: I’m in my second year, doing an integrated masters in biology at the University of Sheffield. My interests are pretty all over the place, but mostly I’m focused on behaviour and the functions that drive it (sexual selection, environment, natural selection, etc.). Other key interests are ethics, and turning reality into mathematical models. So far, I’ve done lots of projects as part of my course. But my favourite two are the ones where the instructions were “think of a plausible study to do, and then do it”. Obviously, I went big because for some reason I seem to keep making my life more difficult. As I’m only in my second year, my projects may have some bias issues. However, I did try to make them as scientific as I possibly could under the circumstances.

Let’s talk about fish: Before setting off for uni, I did a small project in the summer with twenty Danio rerio (zebrafish). Zebrafish are very smart because they have large brains for their size, they’re only ~4cm long, and can learn to differentiate between colours and patterns in exchange for rewards. For my first test, I used a small tank with red and green sides to test each fish individually each day for a few weeks. Because I wasn’t happy with my results, I redid this project in my first year of uni.

The Question: Do Danio rerio prefer food rewards or social rewards for visual tests?

How: I built a T-maze with one blue fork and one red fork. Red=good. I had two groups of fish: one that I fed when they chose the red fork and one that got to see a friend. All the fish were housed in separate, large plastic cups (they must hate me so much) so I could tell them apart and see their individual learning curves. Here are some pictures:

You can see the T-maze on the left. On the right is a graph of my results. Notice how the social rewarded fish (black line) were slightly more likely to chose the correct answer and get rewarded each day. However, all the up and down lines are error bars. They show that whilst the mean performance of all the fish improved, the actual numbers are all over the place and tangled with the food reward. When you see a graph that looks like this, it often means that the results weren’t different enough to mean anything significant.

What did I find: not much. I got graphs and the fish definitely learned. It does look like social rewards did better at it, but I did some statistical tests which said that the tiny difference between them is too little to mean anything: basically, it could just be due to random variation–what some people call luck.

The Story: Okay, so each scientific paper tells a story, no matter how complicated or wordy they are. Just by looking at the sections of a paper you can easily see the story of the study done. There’s a summary (usually called the abstract), which tells you the basics. And then it gets into detail with why (the introduction), how (the methods), what they found (the results), and what this means for the world (the discussion). I’ve come to really love the layout of a paper. When it’s done well, everything is right there and easy to find–there are handy pictures to explain all the numbers, references to back up any statements they didn’t find in their results, and cool ideas for the future. It’s like a neat little puzzle of hundreds of brains: a scientific poem.

Let’s talk about stick insects that spray poison acid irritant: Yeah, I know what you’re thinking: “Really Sonora? What is it with all the bugs??” I like bugs. Insects are amazing. Especially these guys, which spray impressive volumes of a white irritant when predators try to eat them. Or when I touch them, so believe me when I say it’s a highly effective defence mechanism (you get engulfed in a cloud of an incredibly foul smell–it’s awful). Anisomorpha paromalus is an aposematic insect, this means it has warning stripes to tell predators they should think twice before trying to eat it. The cool thing is that the babies don’t have stripes–they’re camouflaged. So I put some bugs in boxes and watched them to see if they had different behaviour based on their age. Turns out they do!

The question: Does Anisomorpha paromalus have different hiding behaviours depending on their age and colour? Also, do they prefer hiding closer or further away from other insects?

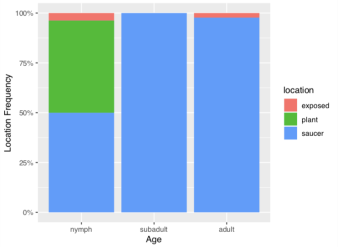

How: I used a total of 35 insects for this study! That’s ten nymphs (<3cm babies), ten subadults (4-5cm juveniles), and fifteen adults (well… ten females and five males). I used two large, separate boxes with three ‘hiding’ places: plants, under saucers, and exposed in plain view. (Cool fact! Once they mate, the male stays attached to the female until they die, sitting comfortably on her back since he’s only 2/3 her size. This means ten of my adults actually behaved like five because they were very attached to each other.) Every morning I recorded each individual’s hiding place and how far away they were from the nearest insect of each age group. It sounds complicated, but I promise it’s not. I did this for eight days and ended up with 238 observations. It was a LOT of numbers. Here are some pictures and pretty graphs:

You can see the average distances that each age group chose to hide from each other on the left, and the locations where each age group hid on the right! I’m really proud of how pretty these turned out–you can tell I at least learned something over the last year…

What did I find: The subadults behaved almost exactly like adults, and liked to be in large groups along with the adults, despite still having no warning stripes. The adults and the subadults hid in clumps under the saucers. The tiny nymphs split their time between the saucers and the plants and didn’t seem to have a preference for how close they were to other insects. I think this is really cool because it means that there must be a point in a nymphs life where it gets big enough that in order to survive it has to change its behaviour. Why do I think this? Survival until reproduction is the MOST important thing for every single living thing. These insects wouldn’t exist if they couldn’t survive, therefore their behaviour should always be beneficial for survival and reproduction.

The key rules you should follow when writing a scientific paper/report:

- Always reference. Always. Reference anything and everything that you didn’t discover. The more references the better. What a lot of people don’t know is that there are loads of referencing styles. Many first years get marked down because they use lots of different styles in one paper. Don’t do that. Always stick to one style. If you google “referencing styles”, there are loads of guides which explain the differences between them better than I ever could.

- Do your research. Think the author of a paper you’re relying on could be a little too confident with their theories? Look to see if there are counter-arguments. Usually, there are and thinking about both will almost always make what you’re writing better.

- Proofread! I’m pretty sure every lecturer I’ve ever had has told us all more than once that we need to do this. Obviously, they care a lot about it, which usually means we should too.

- If you’re writing up a project you did, then your hypothesis is super important! In the past, I’ve forgotten to state my hypothesis clearly (Literally, “I/we hypothesise X” would have sufficed…). Don’t do that. Saying what the question is and what you think will happen is telling the reader why they should read your project/study–it’s the equivalent of making the reader care in a novel. Make them care.

- Make it concise. Flowery words and elegant descriptions are unnecessary here. Your readers are not there for the words, they want the science. If you write it clearly and concisely then it will be easier to understand and take less time to read. Yes, I’m looking at you, MacArthur. I really like warblers. And what you’re talking about is one of the most important ecology theories of all time. But 21 pages?? You only needed like 3.

Whoever you are and whyever you’re here, I hope you enjoyed this scientific ramble. Please tell me if you want to see more things like this in the future, or if I should do more posts on alternative forms of writing (i.e. stuff besides novels)!

I’m going to say it again, sorry: Insects are amazing. I really love them. A lot. You should too.